In the early 1980’s, NASA pursued parallel space-station studies. Marshall Space Flight Center favored a series of space platforms, initially unmanned but human-tended by regular Shuttle missions, that would evolve toward a permanently manned platform. (The Carter Administration had banned all discussion of space stations, so euphemisms were necessary.) Unmanned platforms would be located in both polar and low-inclination orbits. (This was prior to the Challenger accident, and NASA still expected to operate a West Coast launch site for Shuttle launches to polar orbit.) The manned platform would be located in the low-inclination orbit. The platforms would be devoted to space science, primarily microgravity and astronomy for the low-inclination platforms, Earth observation in polar orbit.

Johnson Space Center, on the other hand, had minimal interest in science. It favored a concept called the Space Operations Center, which would be dedicated to the support of in-space operations.

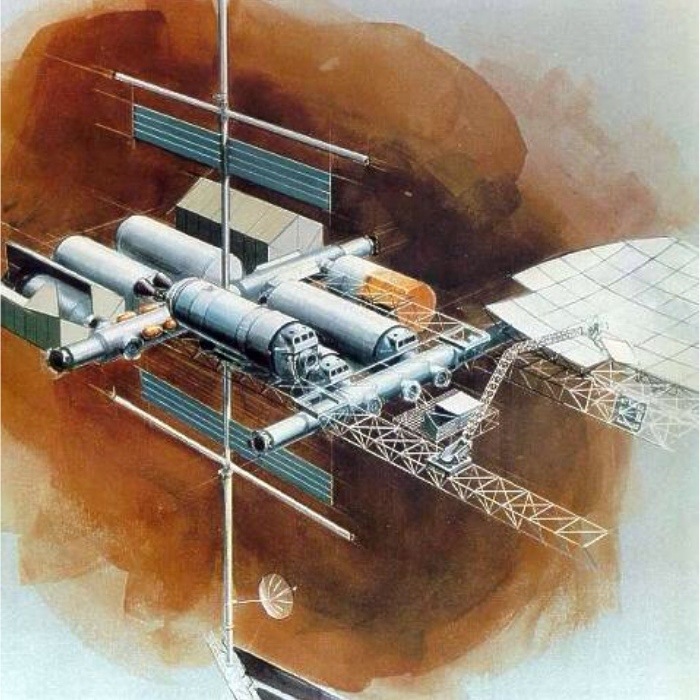

The Space Operations Center would serve as a construction site, propellant and maintenance depot, and operations hub for flights to higher orbits. Planned facilities included a crane, pressurized hangar, and docking ports for manned and unmanned tugs.

The MSFC and JSC studies proceeded in parallel until NASA Headquarters realized the new Reagan Administration might be willing to reconsider the Carter-era “no space station” decision. At that point, the two rival centers were ordered to come up with a unified proposal that could be presented to the President.

The compromise that emerged discarded Marshall’s multiple science platforms for a single station in low-inclination orbit, as favored by JSC. The proposed station would retain most of the operational capabilities desired by JSC, but it would also incorporate Marshall’s science payloads.

There was no question that the combined station was going to be expensive: more expensive than the fiscally conservative Reagan Administration was likely to go for. Faced with a seemingly insurmountable political problem, NASA Administrator James Beggs and his staff fell back on a classic Washington solution: they lied. NASA presented the concept to the President as a station that could be built in four years for $8 billion, deliberately failing to mention that the figure failed to include any of the Shuttle launch costs. It was hoped that by the time the omission was discovered, the project would be underway and momentum would carry it along. To pull off this political maneuver, NASA made sure that Presidential Science Advisor George Keyworth (who would have immediately recognized the deception) was absent from the cabinet meeting where it was presented to the President.

NASA got the approval for the space station it wanted, and Beggs was right that political momentum would carry the station through to completion. The chickens soon came home to roost on Beggs’s lie, however. It quickly became obvious to everyone that the station would cost far more than $8 billion, forcing NASA into a seemingly endless cycle of redesigns which increased the cost even further.

The redesigns finally resulted in an International Space Station that is almost completely devoid of the operational capabilities Johnson Space Center wanted. It did manage to retain the crane, but there was no money for the space construction projects NASA once hoped for. Instead, the chief mission of the International Space Station was simply to build itself.

Station science missions were also cut back drastically to pay for cost overruns. At the same time, however, the station was still officially about science. Preserving the microgravity environment for science experiments became an obsession, resulting in strict limits on operational activities such as dockings and undockings. The orbit of the station was also shifted, due to Russian participation, to a mid-inclination orbit. This orbit, which was necessary to allow for station access from Russian launch sites, has some advantages for Earth observation (it can cover most of the targets that would be seen by a polar platform) but also makes it harder to use the station for launches to deep space or geosynchronous orbit.

In retrospect, combining the MSFC and JSC mission concepts proved to be a bad idea. Moving microgravity experiments off the International Space Station to a co-orbiting free-flyer (a partial return to the original MSFC concept) would free ISS from the onerous microgravity limits and make the station much more useful for commercial and operational missions. Despite occasional recommendations from the user community, however, there has been no political movement in that direction.

An operational space station like the SOC concept would be more valuable today than in the 1980’s. The original Space Operations Center would have been limited by the Shuttle. With the development of new commercial space systems by Boeing, SpaceX, and others, frequent access to space will soon be a possibility. An SOC-like space station serving as a propellant and operations depot would make it much easier for NASA to realize its goals for Beyond-Earth-Orbit exploration and benefit commercial users at the present time. In the 1980’s, NASA thought the SOC could build, launch, and service large communications platforms for Intelsat, but the satellite industry had no interest in such advanced and risky concepts at the time. Today, however, satellite operators are finally starting to take an interest in ideas like on-orbit maintenance and refueling. Bigelow Aerospace is developing large, inflatable space-station modules that could be adapted to fill role’s such as the proposed spacecraft hangar.

So, a commercial Space Operations Center begins to make sense.

The Space Operations Center is 30 years late, but it’s an idea that’s better late than never. Perhaps, even, better late than earlier.

If you could point to a document that has the Carter White House banning discussion of space stations, I’d love to see it. Robert Frosch, NASA AA under Carter, was innovative to a fault. NASA funded a number of studies related to space stations during the Carter years, including SOC, MOTV, 25-kw Power Module, and PEP. SOC reports make clear that the station design drew on a large number of past station studies going back to the 1960s, so there wasn’t really any effort to hide the fact that SOC was a space station.In 1979, NASA HQ stopped station studies at MSFC and JSC to cool the increasingly acrimonious rivalry that had developed between the two field centers. JSC wanted a revolution; MSFC wanted evolution, starting with Skylab reuse. After initially attacking the civilian space program, the Reagan White House came to realize that Shuttle was kind of neat for photo opportunities and signalled mild interest in a Station. It insisted on the lab function for the Space Station because that was the cheapest option and would not imply a commitment to the grand visions of the 1970s. Reagan held the station announcement until the start of the 1984 election year. NASA then produced station designs that combined lab, freeflyers, and shipyard functions. The history of the Station program up until about 1990 was the history of the removal of everything that wasn’t a lab. The idea of a shipyard in space was revived during the Code Z-led LBSS studies, but SEI ambushed Code Z and few of its concepts survived. I plan to write about them on my blog, starting (logically, I think) with the transportation node station Code Z planned for servicing lunar vehicles. dsfp

Robert Frosch was NASA Administrator (not Associate Administrator) under Carter. He may have been “innovative to a fault” but had little interest in space and made no secret of the fact that he would rather be Secretary of Transportation. For that reason, he pushed to involve NASA in automotive research and other areas outside its charter. Upon leaving NASA, he became VP for research at GM.

AA is a NASA HQ mail code. Mail codes are often used as shorthand for the office or title attached to them – AA is the Administrator’s Office. So, when I say NASA AA, I mean NASA Administrator Robert Frosch.

If you have evidence that Frosch involved NASA in automotive research and other areas outside its charter, it would be interesting to be able to read about it. Do you have a citation?

Yes, Frosch headed up the GM Research Labs following the change of Administrations in January 1981. Don’t get confused, however: GMRL wasn’t about cars. In those days, many companies maintained advanced research divisions that poked into all kinds of things. GMRL developed an artificial heart, for example.

Frosch was the most “far out” NASA AA. He funded studies of self-reproducing lunar factories, space colonies, nuclear waste disposal in space, advanced reusable spacecraft, asteroid mining, and much else. He was drawn to advanced research subjects. Frosch was above all an R&D manager.